Volume 28, Issue 4 (Autumn 2022)

Intern Med Today 2022, 28(4): 422-433 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Tehranian F, Nezami H, Maivan M H J, Akbarzadeh Sani J, Hajavi J. Investigating the Frequency of Delta 32 (∆32) Mutation Related to CCR5 Chemokine Receptor in Patients at Gonabad Health Centers, Iran. Intern Med Today 2022; 28 (4) :422-433

URL: http://imtj.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-3932-en.html

URL: http://imtj.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-3932-en.html

Faeze Tehranian1

, Hossein Nezami2

, Hossein Nezami2

, Mohammad Hossein Jafarzadeh Maivan1

, Mohammad Hossein Jafarzadeh Maivan1

, Javad Akbarzadeh Sani3

, Javad Akbarzadeh Sani3

, Jafar Hajavi *4

, Jafar Hajavi *4

, Hossein Nezami2

, Hossein Nezami2

, Mohammad Hossein Jafarzadeh Maivan1

, Mohammad Hossein Jafarzadeh Maivan1

, Javad Akbarzadeh Sani3

, Javad Akbarzadeh Sani3

, Jafar Hajavi *4

, Jafar Hajavi *4

1- Infectious Diseases Research Center, Student Research Committee, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

2- Department of Epidemiology and Biostatics, Student Research Committee, Faculty of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

3- Allameh Bahloul Gonabadi Hospital, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

4- Department of Microbiology, Infectious Diseases Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Gonabad University of Medical Science, Gonabad, Iran. ,hajavi.jaf@gmail.com

2- Department of Epidemiology and Biostatics, Student Research Committee, Faculty of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

3- Allameh Bahloul Gonabadi Hospital, Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Gonabad, Iran.

4- Department of Microbiology, Infectious Diseases Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Gonabad University of Medical Science, Gonabad, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 3401 kb]

(760 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1423 Views)

Full-Text: (1211 Views)

Introduction

Chemokines play an important role in the development and homeostasis of the immune system because of their ability to stimulate the migration of cells, especially leukocytes. Meanwhile, they are involved in all protective or destructive immune and inflammatory reactions. However, chemokine-driven white blood cell migration also contributes to diseases with immune or inflammatory components, including autoimmunity, allergies, chronic inflammatory diseases, cancer, and many others [1].

Chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) is a heptameric chemoreceptor of the G-coupled protein family. This receptor is created in inflammatory conditions and plays an important role in attracting leukocytes involved in the body’s defense system [2].

HIV infection as an important social problem endangers the health of society. Despite the extensive efforts and plans of the World Health Organization (WHO), the high spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease has always caused economic, social, and health losses [3].

HIV uses different chemical receptors to enter the cell, including CCR5 and CXCR4 [3]. CCR5 is the most important common receptor in the early stages of infection, and most people infected with this virus have been infected only in this way [4, 5]. Also, the transmission of this virus from one person to another is almost exclusively limited to this receptor [3].

Genetic studies demonstrate that this gene contains 4 exons on chromosome number 3 [6], but only exon 4 can be expressed. Some individuals have a genetic mutation of 32 base pairs (bp) (∆32) in the gene exon of this receptor [3]. People with the ∆32 mutations do not express the CCR5 molecule on the surface of their cells, or they express this molecule’s non-functional and incomplete form. Accordingly, considering the importance of the CCR5 receptor in creating appropriate chemotaxis of immune cells and also its role in the infection of T lymphocytes and macrophages with HIV, ∆32 mutations in the gene of this molecule can change the function in immune cells and also relative resistance to HIV [7]. The frequency of this mutation is different in various geographical regions and ethnicities [6]; therefore, it is important to study this molecule from an epidemiological point of view. The role of CCR5 in the disease is different depending on specific factors, such as the pattern of the disease, the geography of the samples, and the studied blood group [8].

According to the conducted research, the lack of CCR5 in people is not felt because of the compensation by other chemical receptors and their ligands, and people can grow normally [9]. When a person is homozygous for the CCR5-∆32 mutation, as no receptor is expressed on the surface of the cells, it is resistant to HIV, and when a person is heterozygous, a small number of receptors are expressed on the surface of the cell, which reduces the progression of the disease [10] or causes a delay in contracting HIV [11].

Successful applications of ligand-based models and recent insights into HIV mechanisms have initiated a new strategy aimed at preventing viral adhesion and spread. A promising approach is based on the use of agents that can stop the interaction of viral proteins with the host cell membrane receptor CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 receptors. The CCR5 receptor may also be effective in the development of many other diseases, including cancers, hepatitis, influenza, and autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis [3, 8, 12-14].

Considering the importance of ∆32 mutations in creating resistance to various diseases, especially HIV infection, this study aims to investigate the prevalence of this mutation in people referring to Gonabad Health Center in Iran, given the existing conditions.

Materials and Methods

In this descriptive cross-sectional research, the study population was healthy individuals from Gonabad City, Iran, who passed the following inclusion criteria: being over 18 years old and not suffering from diseases, such as diabetes, hepatitis, autoimmune diseases, and so on. Using the purposive sampling method, 293 people were included in the study. Sampling is done with the coordination of the Health Vice-Chancellor of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences from the visitors to the health center after fully explaining the plan and the importance of the issue and obtaining written consent after entering the study along with after performing a rapid test (ABON kit) based on immunochromatography technology. An amount of 5 mL of venous blood in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid anticoagulant samples was taken from individuals and the samples were transferred to the immunology laboratory of paramedical faculty in cold conditions. DNA extraction was done via the column method (Carmania Parsgene Company kit) and was sterile. SubSubsequently, the mutation with the molecular

Polymerase chain reaction (PRC) method was investi gated using the kit by Carmania Parsgene Company. The results were analyzed after running the PCR product of the samples on a 3% agarose gel and observing the presence or absence of the band related to DNA.

Data analysis

The collected data were entered into the SPSS software, version 22, and after ensuring the correctness of the data entry, qualitative variables were described with frequency distribution tables (frequency and frequency percentage) while quantitative data were expressed with Mean±SD.

The chi-square test was used to compare the frequency of observations in the levels of qualitative variables. In this study, we considered the significant level of 0.05.

Results

The present study was conducted to investigate the frequency of Δ32 mutations related to the CCR5 chemokine receptor in patients of Gonabad Health Center (Iran) and its relationship with demographic characteristics and some diseases from 2017 to 2018. In this study, the data of 293 people were analyzed. The mean age of the subjects was 53.22±10. 84 years. A total of 65(23.2%) women and 225(76.8%) men participated in the study.

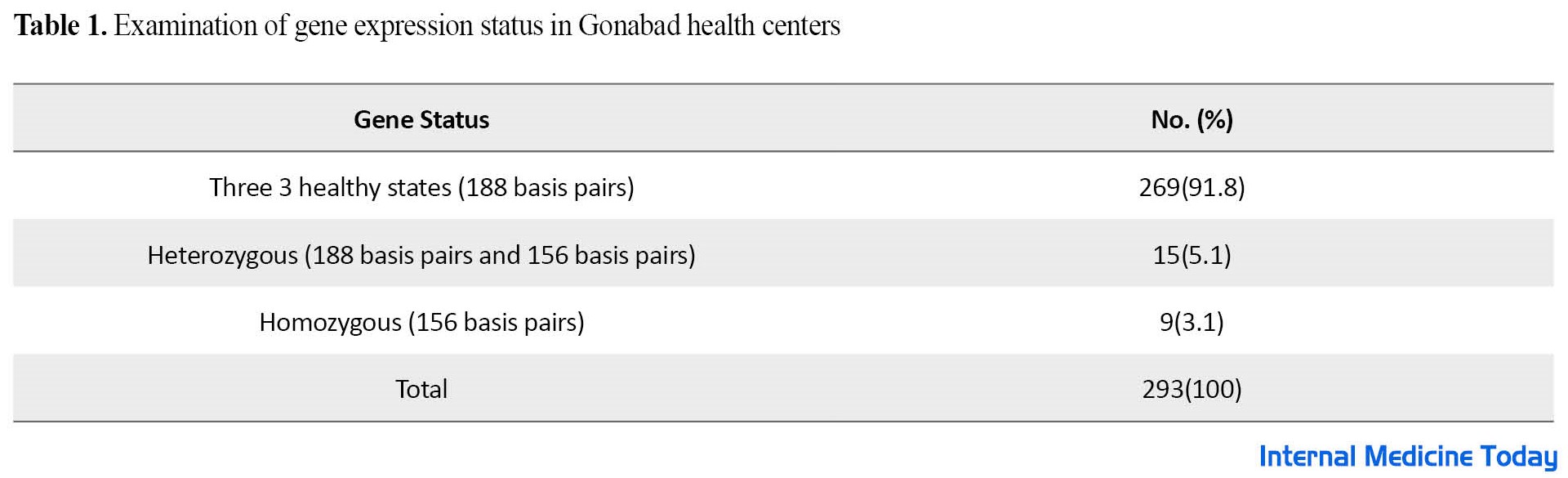

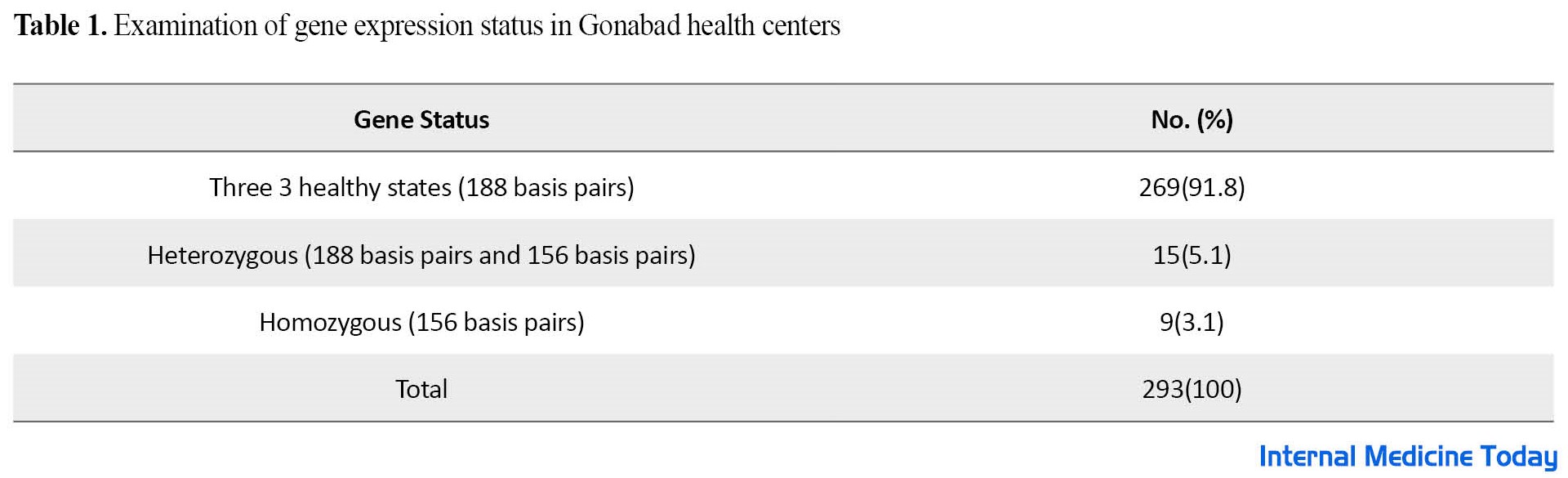

As shown, among 293 people who were referred to the Gene Health Center, 269(91.8%) were 3 healthy states 188 bp), 15(1.5%) heterozygous (188 bp and 156 bp), and 9(1.3%) were homozygous (156 bp), respectively (Table 1).

According to Table 2, the chi-square test results showed no significant relationship between the gene variable and demographic variables (smoking, alcohol consumption, gender, and diseases (diabetes, cancer, and hepatitis).

Discussion

According to the statistics of WHO at the end of 2018, about 37. 9 million people worldwide were infected with HIV. Iranians are considered a mixed Caucasian population with several reasons for their wide genetic diversity [12]. On the other hand, according to previous studies in Iran, considering the geographical conditions and different ethnicities, ∆32 mutation has a different prevalence.

Considering the importance of this receptor in the treatment and prevention of HIV, the present study was conducted to investigate the frequency of mutations related to the CCR5 chemokine receptor in the patients of Gonabad Health Center in 2017 and 2018.

The results showed that out of 293 people who referred to the health center, 269 people (91.8%) had a healthy gene without mutation (188 bp), 15 people (5.1%) had heterozygous mutations (188 bp and 156 bp), and 9 people (1.3%) had a homozygous mutation on both alleles of CCR5 (156 bp).

In contrast to our research, the study conducted by Esmailzadeh et al. on 200 healthy people in Zanjan City, Iran showed that only 1 person (0.5%) was homozygous for this mutation [13]. In our study, heterozygous subjects were 1.5%, while in the study conducted by Omrani et al. on 190 healthy individuals in Urmia City, Iran, the frequency of ∆32 heterozygous mutations was 2.1% [14].

Contrary to our study, the ∆32 heterozygous mutation in Northern Europe is related to the Caucasian population with 16% heterozygous and 1% homozygous, and it is 15% to 16% in Finland, Sweden, Iceland, and Northern Russia [15, 16]. This frequency decreases from 10% in central and western European countries to 4% to 6% in Southern Europe (Greece and Portugal) [15, 17]. Heterozygous mutation in Southern Europe is almost similar to our study (1.5%).

The study conducted in Russia on 300 healthy people showed that in terms of ∆32 mutations, 79 people (18. 33%) were heterozygous and 7 people (67.1%) were homozygous [18]. The heterozygous mutation was 3 times compared to our study, but the homozygous mutation was less than our study.

The study conducted by Gharagozloo et al. on 395 healthy individuals in Fars Province, Iran showed that 97. 2% of the individuals were healthy, 2.8% were heterozygous, and no homozygous individuals were identified with ∆32 mutations [12].

The study of Govorovskaya et al. aimed to investigate the frequency of CCR5-∆32 mutation in Russian, Tatar, and Bashkir populations of Chelyabinsk Province, Russia, 7 homozygous and 79 heterozygous individuals were identified [18]. In a cross-sectional study by Badie et al., among 200 people with HIV who were referred to Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran City, Iran, and their disease was confirmed, 194 patients were randomly included in the study, of which only 8 were heterozygous for CCR5-∆32 and no homozygotes were detected [19]. Unlike the present study, a cross-sectional study in the UAE and Tunisia conducted by Al-Jaberi et al. showed that this mutation was rare, so no homozygous was found in the studied population, and among the Emirati people, only 1 person and among Tunisian merely 4 heterozygotes were identified [6]. A meta-analysis study published in Denmark by Prahalad et al. acknowledged that these results strongly suggest that the CCR5-∆32 allele protects Europeans against the disease, and individuals homozygous for this mutation have a greater protective effect compared to the heterozygous [20]. As shown in the above studies, the prevalence of this mutation can be different in different geographical areas and ethnicities.

In contrast to our study, Ruiz-mateos et al. confirmed and extended the role of CCR5-∆32 as a predictive factor for survival in HIV infection as well as prolongation of survival in people who received a combination of antiretroviral therapy; however, no homozygous mutation was found in this study [21].

The results of a cross-sectional study conducted by Heydarifard et al. show that the ∆32 mutation in heterozygous individuals does not affect their susceptibility to HIV infection [22].

In a review study, Zare Bidaki et al. showed that based on the available data, it is possible that the CCR5-∆32 mutation is not common in the normal population of Iranians [23].

According to the results of the above-mentioned studies, the effectiveness of the CCR5-∆32 mutation against various diseases, especially HIV, is not aligned with the present study, and it can probably be due to different geographical regions or different ethnicities, or even the difference in the number of study samples.

The results obtained from the present study do not show any significant relationship between the gene variable and the demographic variables (smoking, alcohol consumption, gender, and diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and hepatitis). Also, there is no relationship between the gene variable and the variables of age, height, and weight and these results are in line with some of the studies mentioned above.

Conclusion

The results of the study show that the rate of homozygous mutation in the Gonabad Region, Iran, in the studied population is higher than in similar studies, and more epidemiological and molecular studies are needed for better conclusions. According to the results of the present study, the importance of this mutation in the CCR5 receptor in blood donors who are homozygous in this regard, and these people can be candidates for participating in stem cell-based experiments to create a therapeutic window or even as a method to prevent people from contracting HIV.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GMU.REC.1398.119). Ethical considerations for conducting this research have been observed throughout all stages of conducting the research.

Funding

This study was carried out with the financial support of the Deputy of Research and Technology (Code: 1-1845-10/A) of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

The main idea and specialized experiments: Jafar Hajovi; Data analysis: Hossein Nizami; Study design and data collection: All authors; Critical review of the manuscript and final review: Jafar Hajovi, Hossein Nizami, and Faezeh Tehranian.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors and presenters of the project would like to express their gratitude to all the people who helped us with their cooperation and kindness in carrying out this project. Also, the authors are grateful to the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences for their financial and spiritual support in carrying out this project.

References

Chemokines play an important role in the development and homeostasis of the immune system because of their ability to stimulate the migration of cells, especially leukocytes. Meanwhile, they are involved in all protective or destructive immune and inflammatory reactions. However, chemokine-driven white blood cell migration also contributes to diseases with immune or inflammatory components, including autoimmunity, allergies, chronic inflammatory diseases, cancer, and many others [1].

Chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) is a heptameric chemoreceptor of the G-coupled protein family. This receptor is created in inflammatory conditions and plays an important role in attracting leukocytes involved in the body’s defense system [2].

HIV infection as an important social problem endangers the health of society. Despite the extensive efforts and plans of the World Health Organization (WHO), the high spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease has always caused economic, social, and health losses [3].

HIV uses different chemical receptors to enter the cell, including CCR5 and CXCR4 [3]. CCR5 is the most important common receptor in the early stages of infection, and most people infected with this virus have been infected only in this way [4, 5]. Also, the transmission of this virus from one person to another is almost exclusively limited to this receptor [3].

Genetic studies demonstrate that this gene contains 4 exons on chromosome number 3 [6], but only exon 4 can be expressed. Some individuals have a genetic mutation of 32 base pairs (bp) (∆32) in the gene exon of this receptor [3]. People with the ∆32 mutations do not express the CCR5 molecule on the surface of their cells, or they express this molecule’s non-functional and incomplete form. Accordingly, considering the importance of the CCR5 receptor in creating appropriate chemotaxis of immune cells and also its role in the infection of T lymphocytes and macrophages with HIV, ∆32 mutations in the gene of this molecule can change the function in immune cells and also relative resistance to HIV [7]. The frequency of this mutation is different in various geographical regions and ethnicities [6]; therefore, it is important to study this molecule from an epidemiological point of view. The role of CCR5 in the disease is different depending on specific factors, such as the pattern of the disease, the geography of the samples, and the studied blood group [8].

According to the conducted research, the lack of CCR5 in people is not felt because of the compensation by other chemical receptors and their ligands, and people can grow normally [9]. When a person is homozygous for the CCR5-∆32 mutation, as no receptor is expressed on the surface of the cells, it is resistant to HIV, and when a person is heterozygous, a small number of receptors are expressed on the surface of the cell, which reduces the progression of the disease [10] or causes a delay in contracting HIV [11].

Successful applications of ligand-based models and recent insights into HIV mechanisms have initiated a new strategy aimed at preventing viral adhesion and spread. A promising approach is based on the use of agents that can stop the interaction of viral proteins with the host cell membrane receptor CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 receptors. The CCR5 receptor may also be effective in the development of many other diseases, including cancers, hepatitis, influenza, and autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis [3, 8, 12-14].

Considering the importance of ∆32 mutations in creating resistance to various diseases, especially HIV infection, this study aims to investigate the prevalence of this mutation in people referring to Gonabad Health Center in Iran, given the existing conditions.

Materials and Methods

In this descriptive cross-sectional research, the study population was healthy individuals from Gonabad City, Iran, who passed the following inclusion criteria: being over 18 years old and not suffering from diseases, such as diabetes, hepatitis, autoimmune diseases, and so on. Using the purposive sampling method, 293 people were included in the study. Sampling is done with the coordination of the Health Vice-Chancellor of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences from the visitors to the health center after fully explaining the plan and the importance of the issue and obtaining written consent after entering the study along with after performing a rapid test (ABON kit) based on immunochromatography technology. An amount of 5 mL of venous blood in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid anticoagulant samples was taken from individuals and the samples were transferred to the immunology laboratory of paramedical faculty in cold conditions. DNA extraction was done via the column method (Carmania Parsgene Company kit) and was sterile. SubSubsequently, the mutation with the molecular

Polymerase chain reaction (PRC) method was investi gated using the kit by Carmania Parsgene Company. The results were analyzed after running the PCR product of the samples on a 3% agarose gel and observing the presence or absence of the band related to DNA.

Data analysis

The collected data were entered into the SPSS software, version 22, and after ensuring the correctness of the data entry, qualitative variables were described with frequency distribution tables (frequency and frequency percentage) while quantitative data were expressed with Mean±SD.

The chi-square test was used to compare the frequency of observations in the levels of qualitative variables. In this study, we considered the significant level of 0.05.

Results

The present study was conducted to investigate the frequency of Δ32 mutations related to the CCR5 chemokine receptor in patients of Gonabad Health Center (Iran) and its relationship with demographic characteristics and some diseases from 2017 to 2018. In this study, the data of 293 people were analyzed. The mean age of the subjects was 53.22±10. 84 years. A total of 65(23.2%) women and 225(76.8%) men participated in the study.

As shown, among 293 people who were referred to the Gene Health Center, 269(91.8%) were 3 healthy states 188 bp), 15(1.5%) heterozygous (188 bp and 156 bp), and 9(1.3%) were homozygous (156 bp), respectively (Table 1).

According to Table 2, the chi-square test results showed no significant relationship between the gene variable and demographic variables (smoking, alcohol consumption, gender, and diseases (diabetes, cancer, and hepatitis).

Discussion

According to the statistics of WHO at the end of 2018, about 37. 9 million people worldwide were infected with HIV. Iranians are considered a mixed Caucasian population with several reasons for their wide genetic diversity [12]. On the other hand, according to previous studies in Iran, considering the geographical conditions and different ethnicities, ∆32 mutation has a different prevalence.

Considering the importance of this receptor in the treatment and prevention of HIV, the present study was conducted to investigate the frequency of mutations related to the CCR5 chemokine receptor in the patients of Gonabad Health Center in 2017 and 2018.

The results showed that out of 293 people who referred to the health center, 269 people (91.8%) had a healthy gene without mutation (188 bp), 15 people (5.1%) had heterozygous mutations (188 bp and 156 bp), and 9 people (1.3%) had a homozygous mutation on both alleles of CCR5 (156 bp).

In contrast to our research, the study conducted by Esmailzadeh et al. on 200 healthy people in Zanjan City, Iran showed that only 1 person (0.5%) was homozygous for this mutation [13]. In our study, heterozygous subjects were 1.5%, while in the study conducted by Omrani et al. on 190 healthy individuals in Urmia City, Iran, the frequency of ∆32 heterozygous mutations was 2.1% [14].

Contrary to our study, the ∆32 heterozygous mutation in Northern Europe is related to the Caucasian population with 16% heterozygous and 1% homozygous, and it is 15% to 16% in Finland, Sweden, Iceland, and Northern Russia [15, 16]. This frequency decreases from 10% in central and western European countries to 4% to 6% in Southern Europe (Greece and Portugal) [15, 17]. Heterozygous mutation in Southern Europe is almost similar to our study (1.5%).

The study conducted in Russia on 300 healthy people showed that in terms of ∆32 mutations, 79 people (18. 33%) were heterozygous and 7 people (67.1%) were homozygous [18]. The heterozygous mutation was 3 times compared to our study, but the homozygous mutation was less than our study.

The study conducted by Gharagozloo et al. on 395 healthy individuals in Fars Province, Iran showed that 97. 2% of the individuals were healthy, 2.8% were heterozygous, and no homozygous individuals were identified with ∆32 mutations [12].

The study of Govorovskaya et al. aimed to investigate the frequency of CCR5-∆32 mutation in Russian, Tatar, and Bashkir populations of Chelyabinsk Province, Russia, 7 homozygous and 79 heterozygous individuals were identified [18]. In a cross-sectional study by Badie et al., among 200 people with HIV who were referred to Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran City, Iran, and their disease was confirmed, 194 patients were randomly included in the study, of which only 8 were heterozygous for CCR5-∆32 and no homozygotes were detected [19]. Unlike the present study, a cross-sectional study in the UAE and Tunisia conducted by Al-Jaberi et al. showed that this mutation was rare, so no homozygous was found in the studied population, and among the Emirati people, only 1 person and among Tunisian merely 4 heterozygotes were identified [6]. A meta-analysis study published in Denmark by Prahalad et al. acknowledged that these results strongly suggest that the CCR5-∆32 allele protects Europeans against the disease, and individuals homozygous for this mutation have a greater protective effect compared to the heterozygous [20]. As shown in the above studies, the prevalence of this mutation can be different in different geographical areas and ethnicities.

In contrast to our study, Ruiz-mateos et al. confirmed and extended the role of CCR5-∆32 as a predictive factor for survival in HIV infection as well as prolongation of survival in people who received a combination of antiretroviral therapy; however, no homozygous mutation was found in this study [21].

The results of a cross-sectional study conducted by Heydarifard et al. show that the ∆32 mutation in heterozygous individuals does not affect their susceptibility to HIV infection [22].

In a review study, Zare Bidaki et al. showed that based on the available data, it is possible that the CCR5-∆32 mutation is not common in the normal population of Iranians [23].

According to the results of the above-mentioned studies, the effectiveness of the CCR5-∆32 mutation against various diseases, especially HIV, is not aligned with the present study, and it can probably be due to different geographical regions or different ethnicities, or even the difference in the number of study samples.

The results obtained from the present study do not show any significant relationship between the gene variable and the demographic variables (smoking, alcohol consumption, gender, and diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and hepatitis). Also, there is no relationship between the gene variable and the variables of age, height, and weight and these results are in line with some of the studies mentioned above.

Conclusion

The results of the study show that the rate of homozygous mutation in the Gonabad Region, Iran, in the studied population is higher than in similar studies, and more epidemiological and molecular studies are needed for better conclusions. According to the results of the present study, the importance of this mutation in the CCR5 receptor in blood donors who are homozygous in this regard, and these people can be candidates for participating in stem cell-based experiments to create a therapeutic window or even as a method to prevent people from contracting HIV.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GMU.REC.1398.119). Ethical considerations for conducting this research have been observed throughout all stages of conducting the research.

Funding

This study was carried out with the financial support of the Deputy of Research and Technology (Code: 1-1845-10/A) of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

The main idea and specialized experiments: Jafar Hajovi; Data analysis: Hossein Nizami; Study design and data collection: All authors; Critical review of the manuscript and final review: Jafar Hajovi, Hossein Nizami, and Faezeh Tehranian.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors and presenters of the project would like to express their gratitude to all the people who helped us with their cooperation and kindness in carrying out this project. Also, the authors are grateful to the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences for their financial and spiritual support in carrying out this project.

References

- Hughes CE, Nibbs RJB. A guide to chemokines and their receptors. The FEBS Journal. 2018; 285(16): 2944-71. [DOI: 10. 1111/febs. 14466] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Upadhyaya C, Jiao X, Ashton A, Patel K, Kossenkov AV, Pestell RG. The G protein coupled receptor CCR5 in cancer. Advances in Cancer Research. 2020; 145: 29-47. [DOI: 10. 1016/bs. acr. 2019. 11. 001] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vangelista L, Vento S. The expanding therapeutic perspective of CCR5 blockade. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017; 8: 1981. [DOI: 10. 3389/fimmu. 2017. 01981] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Venuti A, Pastori C, Lopalco L. The role of natural antibodies to CC chemokine receptor 5 in HIV infection. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017; 8: 1358. [DOI: 10. 3389/fimmu. 2017. 01358] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zhang Y, Chen HF. Allosteric mechanism of an oximino-piperidino-piperidine antagonist for the CCR5 chemokine receptor. Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 2020; 95(1): 113-23. [DOI: 10. 1111/cbdd. 13627] [PMID]

- Al-Jaberi SA, Ben-Salem S, Messedi M, Ayadi F, Al-Gazali L, Ali BR. Determination of the CCR5∆32 frequency in Emiratis and Tunisians and the screening of the CCR5 gene for novel alleles in Emiratis. Gene. 2013; 529(1): 113-8. [DOI: 10. 1016/j. gene. 2013. 07. 062] [PMID]

- Youssef AI, Hassan AA, Mohammed SA, Ahmed HA. Distribution of the chemokine receptor-5 gene in Egyptian breast cancer patients. Benha Medical Journal. 2018; 35(1): 49. [Link]

- Rautenbach A, Williams AA. Metabolomics as an approach to characterise the contrasting roles of CCR5 in the presence and absence of disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(4): 1472. [DOI: 10. 3390/ijms21041472] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Scurci I, Martins E, Hartley O. CCR5: Established paradigms and new frontiers for a ‘celebrity’ chemokine receptor. Cytokine. 2018; 109: 81-93. [DOI: 10. 1016/j. cyto. 2018. 02. 018] [PMID]

- Atzeni F, Boiardi L, Casali B, Farnetti E, Nicoli D, Sarzi-Puttini P, et al. CC chemokine receptor 5 polymorphism in Italian patients with Behcet’s disease. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2012; 51(12): 2141-5. [DOI: 10. 1093/rheumatology/kes238] [PMID]

- Juhász E, Béres J, Kanizsai S, Nagy K. The consequence of a founder effect: CCR5-32, CCR2-64I and SDF1-3’A polymorphism in vlach gypsy population in Hungary. Pathology Oncology Research: POR. 2012; 18(2): 177-82. [DOI: 10. 1007/s12253-011-9425-4] [PMID]

- Gharagozloo M, Doroudchi M, Farjadian S, Pezeshki AM, Ghaderi A. The frequency of CCR5Δ32 and CCR2-64I in southern Iranian normal population. Immunology Letters. 2005; 96(2): 277-81. [DOI: 10. 1016/j. imlet. 2004. 09. 007] [PMID]

- Farshbaf A, Biglari A, Faghihzadeh S, Esmaeilzadeh A. [Frequency of CCR5Δ32 allelic mutation in healthy individuals in Zanjan province (Persian)]. Journal of Advances in Medical and Biomedical Research. 2017; 25(108): 129-36. [Link]

- Omrani D. Frequency of CCR5Δ 32 variant in north-west of Iran. Journal of Sciences, Islamic Republic of Iran. 2009; 20(2): 105-10. [Link]

- Martinson JJ, Chapman NH, Rees DC, Liu YT, Clegg JB. Global distribution of the CCR5 gene 32-basepair deletion. Nature Genetics. 1997; 16(1): 100-3. [DOI: 10. 1038/ng0597-100] [PMID]

- Libert F, Cochaux P, Beckman G, Samson M, Aksenova M, Cao A, et al. he deltaccr5 mutation conferring protection against HIV-1 in Caucasian populations has a single and recent origin in Northeastern Europe. Human Molecular Genetics. 1998; 7(3): 399-406. [DOI: 10. 1093/hmg/7. 3. 399] [PMID]

- Papa A, Papadimitriou E, Adwan G, Clewley JP, Malissiovas N, Ntoutsos I, et al. HIV-1 co-receptor CCR5 and CCR2 mutations among Greeks. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology. 2000; 28(1): 87-9. [DOI: 10. 1111/j. 1574-695X. 2000. tb01461. x] [PMID]

- Govorovskaya I, Khromova E, Suslova T, Alexeev L, Kofiadi I. The Frequency of CCR5del32 mutation in populations of Russians, Tatars and Bashkirs of Chelyabinsk Region, Russia. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2016; 64(Suppl 1): 109-12. [DOI: 10. 1007/s00005-016-0429-3] [PMID]

- Badie BM, Najmabadi H, Djavid GE, Kheirandish P, Payvar F, Akhlaghkhah M, et al. Frequency of CCR5 delta 32 polymorphism and its relation to disease progression in Iranian HIV-1 positive individuals: P1200. Clinical Microbiology & Infection. 2010; 16. [DOI:10.15406/jhvrv.2015.02.00059]

- Prahalad S. Negative association between the chemokine receptor CCR5-Delta32 polymorphism and rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis. Genes and Immunity. 2006; 7(3): 264-8. [DOI:10. 1038/sj. gene. 6364298] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ruiz-Mateos E, Tarancon-Diez L, Alvarez-Rios AI, Dominguez-Molina B, Genebat M, Pulido I, et al. Association of heterozygous CCR5Δ32 deletion with survival in HIV-infection: A cohort study. Antiviral Research. 2018; 150: 15-9. [DOI: 10. 1016/j. antiviral. 2017. 12. 002] [PMID]

- Heydarifard Z, Tabarraei A, Moradi A. Polymorphisms in CCR5Δ32 and Risk of HIV-1 Infection in the Southeast of Caspian Sea, Iran. Disease Markers. 2017; 2017: 4190107. [DOI: 10. 1155/2017/4190107] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zare-Bidaki M, Karimi-Googheri M, Hassanshahi G, Zainodini N, Arababadi MK. The frequency of CCR5 promoter polymorphisms and CCR5 Δ 32 mutation in Iranian populations. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 2015; 18(4): 312-6. [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Basic Medical Science

Received: 2022/09/12 | Accepted: 2022/11/23 | Published: 2022/09/23

Received: 2022/09/12 | Accepted: 2022/11/23 | Published: 2022/09/23

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |